Buenos Aires We have worked with Edward Gramlich. When he was at the Federal Reserve Board as a Governor under President Clinton we had hopes that he would move the body forward. During his time it goes without saying that he was one of the few up there that would give ACORN and our leaders either an audience or a hearing.

The New York Times brought these memories back with an on-point and poignant article about Gramlich having made the right call in a recent book on the sub-prime crisis. Once again it seems ACORN and Gramlich were on the same side. The other part of the article was direr and read uncomfortably on the internet from Buenos Aires, because it seemed to be the long goodbye on the way to a final farewell. At 68 I guess there is a life well lived to note, but it all seems so short when there is so much left to fight and so few friends to share the struggle, so for my part, and all of our part at ACORN, this is one fellow traveler we will wish was still in the traces with us as we try to make sure that we learn the right lessons in the immediate mortgage crises, rather than letting greed, techno-babble, and homeless money ending up as another burden borne down the road by the poor.

Here’s the piece from the Times:

Being Right Is Bittersweet for a Critic of Lenders

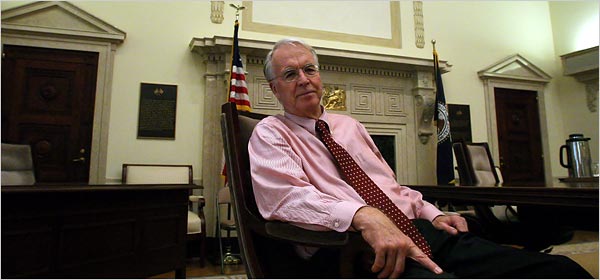

Jamie Rose for The New York Times

By MICHELINE MAYNARD

Published: August 18, 2007

This should have been Edward M. Gramlich’s moment.

For more than a decade, even before he was named a governor of the Federal Reserve Board in 1997, Mr. Gramlich was warning of dangers in the housing market, a stance that has made him a sought-after expert in the current crisis.

As chairman of the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation, he urged legislators to better protect consumers against predatory lenders, and toughen regulation of mortgage lenders and banks. Nonetheless, his efforts met resistance within the Fed and on Capitol Hill, and even he admits he could have pushed earlier for reform.

Still, in June, he published a timely book, “Subprime Mortgages: America’s Latest Boom and Bust,” that has linked his name once more to the home loan situation, which he says he never could have expected would become so dire.

By rights, Mr. Gramlich would be entitled to be at the center of the debate. But instead, he is fighting for his life.

After falling ill during a trip to Africa in March, he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, an advanced cancer of the white blood cells, for which treatment is arduous and survival rates low.

It is his second bout with the disease. In 2002, while at the Federal Reserve, he was diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia, a more treatable form of blood cancer. After chemotherapy, he went into remission.

Mr. Gramlich, 68, has been offered a highly experimental treatment, overseen by his doctors at Johns Hopkins Medical Center in Baltimore, to help fight his new cancer, for which he already has undergone one round of procedures. But he has decided to forgo it, at least for now.

Though doctors cannot say with certainty how long he will live without the therapy, his wife estimates it may be no more than a few months.

“It’s a hard decision,” Mr. Gramlich, known as Ned, said in a telephone interview this week from his home in Washington (unable to go out in crowds, he now sees few visitors except family). “This whole thing, I have to say, is tremendously unfair, that it hit. But it did hit, and what do you do now? You make the best of it.”

As to be expected from the author of a book on cost-benefit analysis, as well as the former chairman of the federal loan board for the airline industry, Mr. Gramlich is weighing the pros and cons of his own situation with an economist’s detachment.

In this case, he balanced the quality of life, or lack thereof, that the treatment might afford. “It’s a great maybe,” Mr. Gramlich said.

With remission unlikely, the experimental treatment might extend his life, “but maybe not, and it could shorten it,” he said. Moreover, Mr. Gramlich, who is already weak from his disease, was told he would probably become even sicker as the treatment progressed.

“I just didn’t want to do it,” Mr. Gramlich said. He added that he might consider other treatment options, but he and his wife also plan to investigate hospice care soon.

Though his decision was made pragmatically, it has still shaken his friends. “For him to talk about going out is a lot easier than it is for all of us,” said Roger W. Ferguson, a former vice chairman of the Federal Reserve who served with Mr. Gramlich, and is now chairman of Swiss Re America Holding, the United States branch of the global insurer.

But Mr. Gramlich’s conclusion was “in character” with his analytical side, Mr. Ferguson added.

Mr. Gramlich’s decisions recall those of the author and political columnist Art Buchwald. In February 2006, he chose to discontinue receiving dialysis for kidney disease.

Although told he might be dead within weeks, Mr. Buchwald lived on for nearly a year, writing another book, and playing host to famous friends at his hospice bedside. He died in January, and marked his passing with a video obituary for The New York Times’s Web site that began with this declaration: “I’m Art Buchwald, and I just died!”

Mr. Gramlich acknowledged the similarities: “He essentially made the decision that treatment was awful, he couldn’t abide it, and so, to hell with it, let’s see what happens.”

While not approaching his fate with quite so much humor, Mr. Gramlich is displaying at least as much candor.

This month, he and his wife, Ruth, shared his decision not to seek further experimental treatment in a newsletter they had posted on a Web site called CarePages, which allows patients to update family and friends about their treatment, and receive messages of support.

More than 350 people have logged in to read Mr. Gramlich’s CarePage, which Mrs. Gramlich said had spared the family the time and emotional trauma of notifying people themselves.

“You’re overwhelmed by caring people who want to know what’s going on,” Mrs. Gramlich said.

Readers have included family friends, former government colleagues and associates at the University of Michigan, where Mr. Gramlich served as dean of its public policy school and, more recently, as acting provost in 2005 and 2006.

Along with health updates, the entries have shared the family’s emotional frustration.

“We were brought up by the older generation to be much less forthcoming about these things, both the facts and the emotions,” Mrs. Gramlich said.

With close friends, “Ned and I would be absolutely honest that this is incurable; it also would be dishonest not to say we’re sad and devastated.”

But his illness has not yet prevented Mr. Gramlich from having his say about the housing market, an interest of his that predates his years at the Fed.

While there, he spoke frequently about the boom in home prices that took place earlier this decade, warning that loans by predatory lenders to low-income buyers were not receiving enough scrutiny.

Their practices, like charging excessive fees and refinancing for the sole purpose of collecting more fees, “jeopardize the twin American dreams of owning a home and building wealth,” he said in a 2002 speech.

Mr. Gramlich said that upon leaving the Fed two years ago, he had planned to write about the housing boom. But his tenure at Michigan intervened, and by the time he completed the manuscript last December, the subprime market was on its way to collapsing, fulfilling his worst policy fears.

Last month, despite his obvious poor health, he spoke at length about potential solutions during a televised panel sponsored by the Urban Institute; he is a senior fellow there, and the institute published his book. (The group’s president, Robert Reischauer, said of Mr. Gramlich: “Ned is to the policy community what an Olympic gold medal decathlete is to the world of sports.”)

He voiced a repeated theme, that more regulation of subprime lenders is needed from the Fed and other agencies. Lately, that is a point the Federal Reserve has made, “but they seem to be alone,” Mr. Gramlich said.

Rather than watch troubled borrowers flounder, he would like to see community groups help them avoid foreclosure, and even purchase homes that could be sold to low-income borrowers. “With very small amounts of money, they could do a world of good,” he said.

He noted the incongruity of the timing of his illness, coming just as an issue so important to him had become front-of-mind for many policy makers. “It’s good news and bad news,” Mr. Gramlich said.

On the downside, his illness is preventing him from making many more appearances to promote his book, since he is susceptible to infection.

But the good news “is that the last thing I ever did was really important,” Mr. Gramlich said. “I really feel I got it right at the end.”