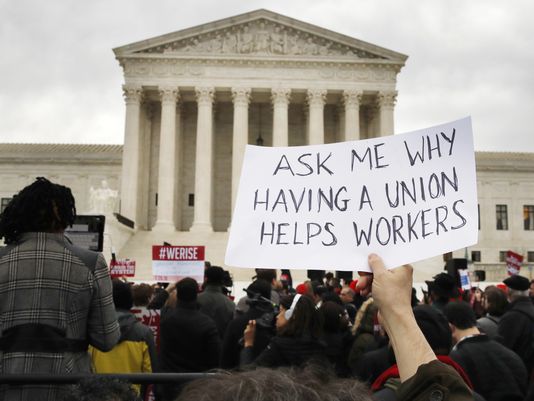

Denver National union strategists and lawyers have doubtlessly been proposing endless alternatives to blunt the impact of the long awaited Janus v. AFSCME verdict of the Supreme Court eliminating the ability for unions in more than twenty states to collect servicing fees from public sector nonmembers for collective bargaining and other functions. The fruits of such labor are already visible in the action by state legislatures in New Jersey and California to mandate workplace access at orientations for union representatives to meet new workers and give them the opportunity to enroll new members. In a select number of states where unions continue to have density and public employees have the ear of lawmakers we are likely to see other initiatives.

Denver National union strategists and lawyers have doubtlessly been proposing endless alternatives to blunt the impact of the long awaited Janus v. AFSCME verdict of the Supreme Court eliminating the ability for unions in more than twenty states to collect servicing fees from public sector nonmembers for collective bargaining and other functions. The fruits of such labor are already visible in the action by state legislatures in New Jersey and California to mandate workplace access at orientations for union representatives to meet new workers and give them the opportunity to enroll new members. In a select number of states where unions continue to have density and public employees have the ear of lawmakers we are likely to see other initiatives.

Some professors have advanced a notion that public authorities directly reimburse unions for collective bargaining functions performed by nonmembers. Their well-intentioned argument is that there are public policy benefits achieved in preventing workplace conflict and public disruption through a functional bargaining regime that seeks compromise and agreement rather than forcing conflict. These benefits inure to the public and the workforce, both those that pay union dues to pay for this work and those workers who can now refuse to make such payments, therefore the public authority should offset such losses by providing resources to the unions to do their jobs.

There is a certain logic there, but it can’t be a good idea for governments to subsidize independent unions. The notion is not unique. In France for example major union federations are directly subsidized by the government based on their percentage of workforce representation. Predictably it has led to lower union dues and a decreased emphasis in enrolling workers as union members. Additionally, in a system that rewards a percentage of membership in a non-exclusive bargaining system, labor is divided as larger federations try to squeeze out smaller unions in order to block their subsidies and viability. All of this may maintain a status quo, but none of it is necessarily in the best interests of workers.

On the other hand, a more practical policy, and one more politically viable in the American context particularly, might be the system practiced by labor courts and their adjudicators using France as an example again. At their discretion labor judges make awards of varying amounts to unions representing workers on disputes before the court that are found to have merit which can range from several hundred euros to several thousand depending on the complexity of the case and the judge’s decision much in the way lawyers are awarded fees. An independent objective party rather than the government itself is subsidizing representation costs of unions on meritorious cases when the workers prevail. Grievance handling is more expensive for most unions than collective bargaining and labor courts with such discretion would hold arbitrary public and private employers accountable while offsetting the costs of unions to provide this service with both public and workplace benefits. The EEOC and the DOL in the United States operates similarly in regard to lawyers’ fees, why not union representation?

Unions face a huge organizing problem now that is all our own, but in bargaining and representation new adaptations might be practicable and win wide support in some areas in the post-Janus world.