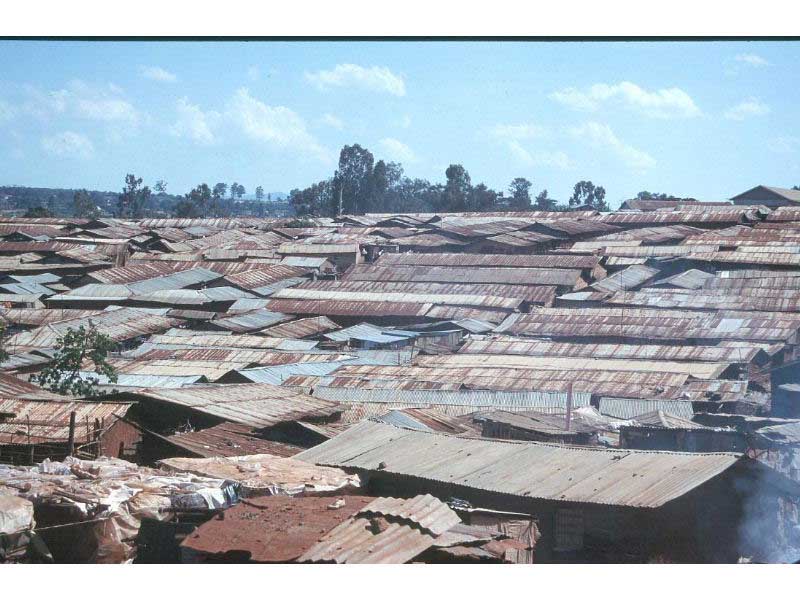

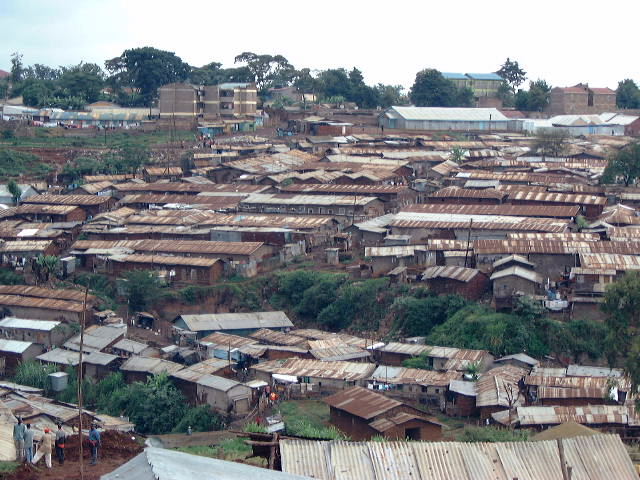

Nairobi Mark Splain is an organizing manager in the SEIU health care division, but he can join me in counting almost 40 years of seniority in the all phases of the work from labor to community and back and forth again. He has joined me in Nairobi (using a week of his vacation!) so that we can see if we can really get our arms and minds around the question of why Kibera, often thought to be the largest slum in Africa with estimates of a million residents, is in fact the way it is.

We plowed through the first day of meetings with one constant question and theme today, especially when we talked to Lawrence Apiyo, chair of the Community Organizers’ Professional Association of Kenya (COPA-K) and employed by the Panoya Trust, Anthony Mburu of the Shelter Forum (an COPA co-chair), Geoffrey Bakhuya, the manager of COPA-Kenya, and then later in the early evening Davinder Lamba of the Mazingira Institute, a board member of Habitat International — Coalition and a long time whistle blower, democracy advocate, and housing researcher and organizer.

The questions we thought were simple enough: Who owns the land under Kibera, and who are the landlords to whom people are paying rent?

The answer was not only simple but also stunning.

The land is public land. In fact the land under Kibera is land owned by the national government and not impacted by the Nairobi City Council at all. Is any of the land railroad land? No, not really and the slither of land that belongs to the railroad is private land because the state railroad has been privatized.

So, we asked repeatedly — and stupidly, we thought — whether the “rents” being paid by people living in the shacks of Kibera were a form of taxes or rents being paid to the government. The answer was “no.” In fact the national government did not admit that there were even people — a million reportedly — living on their land, and neither did they concede that these invisible people were paying rents to anyone for anything. Alice, welcome to wonderland!

Well, who are these landlords? It turns out that they are people less poor than the other people paying, and in the way of these things they are the poor who were there first with — as we say in the USA — boots on the ground. So they staked out small pieces of ground where they were squatting and with a little investment, materials, and sweat equity, they built additional shacks for the newly arrived and then collected rents from them. They saw themselves as “owners” even though this is public land. Davinder made the point that in fact these were “slumlords,” and he called them correctly. Some of these slumlords rented one shack or two, sometimes 10 or 20, and in several amazing cases around 200 shacks! How did they get “control” of this public land? Simple bribes to various officials and then later to investigators and surveyors and anyone else who tried to upset the deal.

So a difficult part of this puzzle was gradually starting to become clearer. There was an organized body in Kibera (a lot of slumlords and even some of the poor renting a desperate corner of their own shack or a room in their hovel) who depended on Kibera staying a slum because this was their livelihood, and they controlled (and bribed it would seem) enough public officials to maintain status quo.

There are then different forces tugging at each other at the very dirt level of the shack floors. One — the property holders — has way more power than the other, and the second– the slum dwellers– particularly the women heads of households who might benefit from new housing construction proposals that are still outstanding and under construction, don’t have an organized voice.

This is a conundrum certainly, but it is not insoluble if there were a mass organization of the majority of slum dwellers in Kibera.

There are many more questions we now have, but gradually we are scratching the surface.

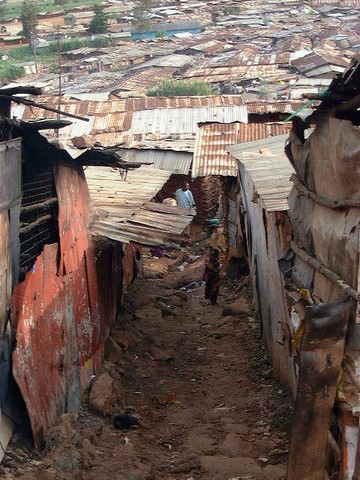

A typical side street in Kibera

Because there are no paved streets in Kibera, the ground underfoot is often wet.