New Orleans I was invited to the lunch held by the ACORN Caucus of Color on the final day of the Year End / Year Begin Meeting. Having arrived on time, I sat at the back table. As the organizers arrived there were a lot of double takes as they saw me there. When we went around and introduced ourselves, I said I was there for the red haired people.

But I was really there because Bertha Lewis, New York ACORN’s Executive Director, who was the outgoing caucus chair, and Steve Bradberry, Louisiana ACORN’s Head Organizer, needed me to explain who George Wiley was so that the Caucus members could fully appreciate the weight of the award. I was honored.

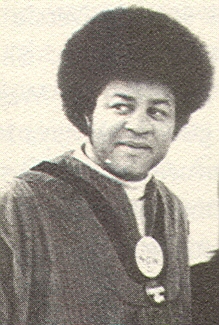

I told them that Dr. George Wiley was a professor of chemistry at Syracuse University and a native of Providence, Rhode Island. He had left the academy to be the deputy director of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, during the civil rights movement. As the movement progressed in the early to mid-60’s George left to figure out a way to go forward that he felt both important and compatible. He spent time at the Poverty Rights Action Center reaching out and talking to people. Welfare recipients were looking to unit from one pocket to another where they were isolated around the country. George pulled them together in a march on June 30th, 1966, to protest cutbacks in Columbus, Ohio. This became the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO). By the time I worked for welfare rights and built the chapters in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1969, NWRO was the largest poor peoples’ organization in the country. I left in mid-1970 to found ACORN with his support as part of the NWRO “southern strategy” to force welfare reform by building a base to challenge Louisiana Senator Russell Long, head of the Senate Finance Committee, and Congressman Wilbur Mills from Arkansas, head of the all-powerful House Ways and Means Committee. Both were blocking welfare reform.

I told them about George’s visit to Arkansas to see ACORN in 1973 as he tried to figure out his next organization. And I told of his tragic death in a boating accident while with his young children on Chesapeake Bay. George did not know how to swim and fell off the boat. It was typical of George that that limitation had never seemed to be an impediment that would stop him from doing what he wanted to do.

With great fanfare, Steve presented the award to Tanya Harris, New Orleans ACORN’s great head organizer. She of course was not there. She was getting more food because the great growth of diversity of the ACORN staff had meant that the Caucus was larger than the loaves and fishes brought together for the lunch.

Bertha came up to me and whispered that I had forgotten something major in my remarks.

I asked if I could say one more thing. I looked over the crowd of more than 200 organizers that were there and I marveled to myself at the diversity of this ACORN rainbow from south Asia to the south Bronx from Puerto Rico to the Dominican Republic from Africa to Birmingham, Fresno, and Salt Lake City. I thought of the fact that there were another couple of hundred on staff who were not seated before me.

I then said that Bertha wanted me to add something that I had overlooked and forgotten to mention. Perhaps it even says something that I had forgotten what might have been so obvious and apparent about George Wiley when he was my boss before ACORN.

George Wiley was a great African-American and a black man.

George Alvin Wiley (1931-1973)