Jakarta 36 Days of Exile

The one thing you heard over and over again before coming to Jakarta is that the traffic may be the worst in the world. Reading V. S. Naipul’s Among the Believers some years ago the passages about endless hours stuck in traffic in Jakarta stayed with me longer than many of the other points he might have had higher hopes of imprinting on the reader. In the face of this constant and ever present danger, the Organizers’ Forum delegation moved like an army on attack. We were up early. We were in the lobby with a vengeance. We moved to the bus as one. And, we were always surprised when we ended up at an appointment in a timely fashion, which was way more often than we had been prepared to believe possible. Through pure good fortune we were often moving in the opposite flow of rush hour. Sailing by we could see the other side of expressways knotted with cars for endless miles. We looked the other way and crossed our fingers.

We arrived at the offices of the Urban Poor Consortium housed in what was, or had been, the residence of its coordinator Wardah Hafidz in a pleasant neighborhood of the city. This was a sophisticated and polished organization which began its meeting with us with a slick, ten minute video presentation providing the context for their work. One could see the actions aimed at preventing the removal of slum housing and watch the police pulling down dwellings with huge ropes and bulldozers. They organized bekak drivers, who pedaled large tricycles as transportation conveyances and had been banned by the city for the sake of appearances we heard and had their bekaks picked up and destroyed by the police.

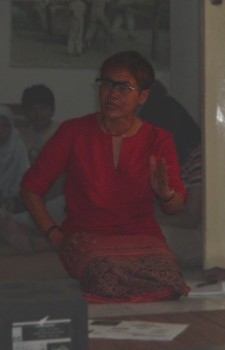

Wardah Hafidz spoke English with a soft, but firm assurance that riveted attention. She had gotten her masters in sociology twenty years before at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana and found her way into organizing and advocacy as she responded to life and conditions in her country upon her return. She spoke the language of community organizing within the framework and funding of an NGO. The organizational chart listed 3 community organizers as part of the staff of 15 as well as researchers, communications people, and collectors in their savings schemes. Their program consisted of mobilizations and direct actions which leveraged the press and other media against the government to try to deliver for their base or at least forestall worst calamities in the face of urbanization and dislocation. It would have been very, very hard not to be impressed with Wardah and her quiet, certain sincerity and firm thoughtfulness. She was as interested in listening to our experience as offering her own. This was an organizer and leader who had thought deeply about what she was building and worried, as we all do, on a daily basis whether she was moving closer or farther from the goal. At the same time you could tell she would be candy to the donor community and would have to be careful to find and stay her course.

It was also clear that they were struggling about where to center the base within the structure of their organization. She shared stories of organizer recruitment which resonated with all of us when she had tried to hire 10 young, recent university students as organizers and plant them to live in the communities and found that only 1 survived as an organizer a year later. She now pulled staff from the communities, and we were impressed when two of them introduced themselves and indicated they were living at different locations under the “big highway,” which meant they were squatters. She used terms like peoples’ organizations and referenced the influence of Alinsky principles, both of which indicated the footprints of Denis Murphy and his troops from the Philippines had passed through here and left their mark on UPC.

We desperately wanted to hear that they were succeeding, but Wardah’s honesty was making clear that there were wins here and there, but that they were still fighting rearguard actions in losing campaigns. When asked if they had been able to win relocation for squatters, which has been the centerpiece of the Philippines campaign model, Wardah said yes for owners and no for squatters. Their work organizing the bekak drivers in the informal economy she described as almost a “guerilla” campaign where they now supported 3000 drivers operating outside of the law, set deeply in urban poor communities.

We had a deep discussion about dues. She and her partners indicated that this had been a constant debate and discussion. It fit their politics but had simply not been part of their experience. She wanted me to commit to bringing someone to help them for a month to learn how to create a dues system. She used her Aceh leverage. I promised I would get back to her and that we would follow-up. She was good! She pushed me hard.

When she put her hand out as we all rose with thanks to say goodbye, she caught me and grabbed my hand, caught my eyes and said, “We have a deal, right?”

It was impossible to not agree that we had a deal, and it would be impossible to not deliver once you had shaken her hand.

- She was very, very good.

September 27, 2005