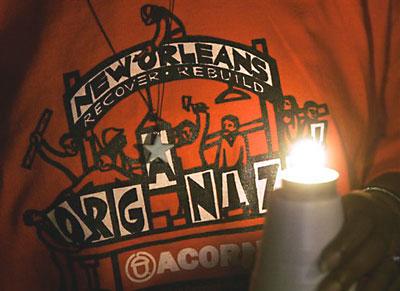

New Orleans At midnight on New Years’ Eve four families stood in front of their houses on Jourdan Avenue in the deepest part of the now famous Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans. The fog was everywhere as it collected from the Mississippi River only blocks away and from the Industrial Canal a mere few feet away from what was left of a limping and failed levee. With them were ACORN organizers and leaders, like Greta Gladney, who had worked to see this night come after four months of fighting all comers since the storm, when the entire area was increasingly written off, seeming to go under for the count time after time, yet spiritedly bouncing back each time.

The weather was not cold, but it was wet and damp. Near midnight when elsewhere in the city fireworks traditionally were exploded, the families instead nodded silently as Scott Hagy, director of ACORN Services, turned the crank on a generator at the back of a panel truck with a giant ACORN logo across the side and letters saying, ACORN Mobile Action Center.

Suddenly there were lights — and life — everywhere in four houses on Jourdan Avenue. These were the first houses to try and come back in an area that until only a few short weeks before had been barred from any entry by armed National Guardsmen and New Orleans Police at barricades on every street, and for reasons, both curious and ominous, had been the last area to be opened to former residents in the wake of the storm. The Lower 9th Ward in this section had been near one of the several breaks in the Industrial Canal, and water had poured in sudden, shocking, and lethal waves obliterating some houses, some families, and moving everything around in its way.

Maybe 2006 will be different?

This New Year’s event even made the news:

Glum New Orleans puts on party face for New Year’s

1/1/2006, 12:21 a.m. CT

By CAIN BURDEAU

The Associated Press

NEW ORLEANS (AP) — As time ran out on 2005, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin summed up how most in this beleaguered city feel about the passing of one of the worst years in its storied past.

“I’m so ready for 2006,” Nagin said.

New Orleans mixed memorials and merrymaking on New Year’s Eve, staging both a jazz funeral procession for hurricane victims and a raucous after-dark party to ring in a much-needed new year.

“Let’s just take a moment to remember all those people who did not make it to 2006,” Nagin told the thousands gathered in the French Quarter as the countdown began.

The French Quarter crowd — numbering in the thousands, but smaller than usual — was an odd mix of locals, volunteers, contract workers and the occasional tourist. Terry Cooney, a 50-year-old Red Cross worker from New Jersey, was dressed in an Irish kilt as he played the bagpipes.

“This is like the first night I’ve seen New Orleans like I remember. Everybody’s in a party mood, half the people are volunteers and half are locals. It’s a good thing,” he said.

Gary Washington, a 37-year-old merchant marine from New Orleans, strolled down Bourbon Street, drink in hand.

“It looks like Hurricane Katrina never came by, looking at the faces,” he said.

Despite the destruction still evident four months after Hurricane Katrina’s violent assault on Aug. 29, the city decided to welcome the New Year with fireworks and concerts. But a thick fog blanketed New Orleans and the fireworks were canceled.

In a twist on Times Square’s dropping of a giant lighted ball, a giant replica of a gumbo pot inched down a pole atop a building on the edge of the French Quarter.

“New Orleans is back open, so come on down and start visiting. That’s the word to get out,” said Brian Kern, an organizer of the New Year’s festivities, which were being funded by private enterprise because the city’s tax income was wiped out by the storm.

Before Katrina, the Big Easy’s all-night bars, haute cuisine, steamboats and romantic French Quarter courtyards made it a favorite New Year’s eve destination for tourists.

This New Year’s celebration, business leaders agreed, was the perfect chance to show the world that New Orleans still knows how to throw a party.

Even the Jazz funeral procession, which began in the afternoon and wound through the Uptown neighborhood, was festive. It drew those along the route into a traditional “second line” parade and made enough noise to bring the curious out of their homes and onto their porches.

“We’re getting into the spirit,” said Sharif Nadir, a 59-year-old writer, as he hugged friends and merged into the second line. “I just hope it puts people into the spirit to rebuild.”

Marc Pagani, a photographer for a bawdy group of majorettes backing up the procession’s brass band, confessed to some discomfort amid the revelry.

“It’s weird to be celebrating when so many people are homeless and miserable,” he said. “But on the other hand, we need to celebrate. It’s kind of half and half for me.”

In the debris-strewn Lower Ninth Ward, the worst hit neighborhood in the city, generators lit up two blocks of the devastated area as a message of hope.

“The symbolism behind this is that we are coming home, the residents of the Ninth Ward are coming home,” said Tanya Harris, a resident and a community organizer for ACORN, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now.

Revelers were urged not to light fireworks out of fear that they would ignite dead vegetation and debris still piled throughout the city or the blue plastic tarps draped over thousands of damaged roofs.